Time to deal with authenticating users in our bookstore application.

This is an onging series of articles. It’s highly recommended you start with part 0!

What is token authentication?

“And why do we even need it?” are two questions you might be asking yourself right now. You’re probably familiar how a simple authentication flow might work in a “regular” Rails app:

- User provides login and password,

- The credentials are checked against a list (e.g. a database) of approved users,

- If the credentials match, a cookie is set on the user’s browser.

This list is of course simplified, but that’s the general idea. But for an API app we can’t use cookies for a couple of reasons:

- The frontend app is completely separate from our API backend - the cookies we set in the browser won’t hit the backend at all.

- There might not even be a browser. I keep stressing this across this whole series of articles, but I feel this bears repeating: anything that can parse JSON should be able to use our app.

Enter JWT

For the above reasons we will use JSON Web Tokens for passing around credentials in our app. A JWT consists of three parts:

- A header, which contains information about the type of the token and the algorithm used. It looks something like this:

{

"alg": "HS256",

"typ":"JWT"

}

- A payload - that’s whatever we want the token to carry around, for example a user’s ID.

{

"userId": 1

}

- A signature, used to ensure that the communication has not been tampered with. A signature is calculated using the HMAC-SHA256 algorithm; without going too deep into the implementation of this, it’s a hash that’s signed with a server-side secret, so the server can verify that it was indeed the one to produce a token.

Thankfully, there’s a Ruby gem to deal with a lot of this for us. It’s called, somewhat unimaginatively for a Ruby gem, jwt. Let’s look at how we can make use of it.

User model

We all knew this had to happen. It happens in almost every Rails project. We need to create a User model and all the stuff around it.

Since this is a very simple app - and we’re learning, so we want to do as much of this by hand as possible! - we’re not going to use anything ready-made. That’s right, remove that gem 'devise' from your Gemfile please.

Rails 4 added the has_secure_password helper to ActiveRecord models, so we’ll use that to extract some pain out of managing passwords. Make sure gem 'bcrypt' is in your Gemfile, because it is required. I’ll lock mine to 3.1.11, but in the future the newest applicable version may of course change.

That’s all we need to create a very simple User:

$ rails g model User email password_digest admin:boolean

Very barebones, but that’s all we need. The migration needs a couple tweaks to look something like this:

class CreateUsers < ActiveRecord::Migration[5.1]

def change

create_table :users do |t|

t.string :email, null: false

t.string :password_digest, null: false

t.boolean :admin, default: false

t.timestamps

end

end

end

Note the NOT NULLs and defaulting to false on the admin flag.

We also need a couple more things in the User model:

class User < ApplicationRecord

has_secure_password

validates :email, presence: true

end

And we’re done here!

JWT encoding

Reading through the docs, we can see that to encode a token using HMAC-SHA256 with a particular secret, we need to do something like this:

JWT.encode payload, hmac_secret, 'HS256'

And to decode,

JWT.decode token, hmac_secret, true, { :algorithm => 'HS256' }

Slightly unwieldy! We can wrap this into a service object.

class JwtService

def self.encode(payload)

JWT.encode(payload, Rails.application.secrets.secret_key_base, 'HS256')

end

def self.decode(token)

body, = JWT.decode(token, Rails.application.secrets.secret_key_base,

true, algorithm: 'HS256')

HashWithIndifferentAccess.new(body)

rescue JWT::ExpiredSignature

nil

end

end

We’ll just use the secret_key_base as our secret - it’s used for cookie signing in regular apps, so it makes sense here. Notice how in decode we’re skipping the second part of what JWT.decode returns - the second part is the header, and we’re not really interested in that. We’re also wrapping it in a HashWithIndifferentAccess - JWT returns hashes that are string-keyed, but I guarantee you that one of us will forget about that later and spend a good long while getting mad.

Note that we’re rescuing from JWT::ExpiredSignature. JSON Web Tokens have some reserved “claims” (keys) - one of those is the exp

claim. When that is set to a timestamp, and it is past that timestamp, JWT will raise this exception. We’ll simply opt to return

nil in such a case and utilize it later.

Big thank you to Ylan Segal for pointing reserved claims out to me!

Let’s drop in a quick test to check everything works:

describe JwtService do

subject { described_class }

let(:payload) { { 'one' => 'two' } }

let(:token) { '...' }

describe '.encode' do

it { expect(subject.encode(payload)).to eq(token) }

end

describe '.decode' do

it { expect(subject.decode(token)).to eq(payload) }

end

end

It should pass, of course. Okay, on to the next thing:

Giving out an authentication token

We need to check an email and password against Users, and if everything is fine - give out an access token. We’ll also add an expiration timestamp to our tokens so they aren’t everliving.

We can use a command object for the authentication and token-generation portion. The command object exposes a simple pattern:

CommandObject.call(arguments)

We’ll decide that our command objects should return an instance of themselves after calling a payload function. They will also publish a result, errors and a success? predicate.

We’ll make ourselves a little BaseCommand class so we don’t repeat ourselves:

class BaseCommand

attr_reader :result

def self.call(*args)

new(*args).call

end

def call

@result = nil

payload

self

end

def success?

errors.empty?

end

def errors

@errors ||= ActiveModel::Errors.new(self)

end

private

def initialize(*_)

not_implemented

end

def payload

not_implemented

end

end

We’ll use ActiveModel::Errors to provide us with a nice clean way to collect errors that might arise in our commands.

Let’s look at the AuthenticateUserCommand now:

class AuthenticateUserCommand < BaseCommand

private

attr_reader :email, :password

def initialize(email, password)

@email = email

@password = password

end

def user

@user ||= User.find_by(email: email)

end

def password_valid?

user && user.authenticate(password)

end

def payload

if password_valid?

@result = JwtService.encode(contents)

else

errors.add(:base, I18n.t('authenticate_user_command.invalid_credentials'))

end

end

def contents

{

user_id: user.id,

exp: 24.hours.from_now.to_i

}

end

end

It’s a mouthful, but the internals are simple as pie: if an user for the e-mail provided exists and the password matches, return a JSON Web Token with a payload of user ID and an expiration timer. Otherwise, append to errors and return nil.

Note that since the payload is time sensitive with the addition of expiration timestamp, to test it properly we’ll need something like Timecop.

With this command object, our auth controller is very simple:

module Api

module V1

class AuthsController < ApplicationController

def create

token_command = AuthenticateUserCommand.call(*params.slice(:user, :password).values)

if token_command.success?

render json: { token: token_command.result }

else

render json: { error: token_command.errors }, status: :unauthorized

end

end

end

end

end

Add a route and you’re golden:

resource :auth, only: %i[create]

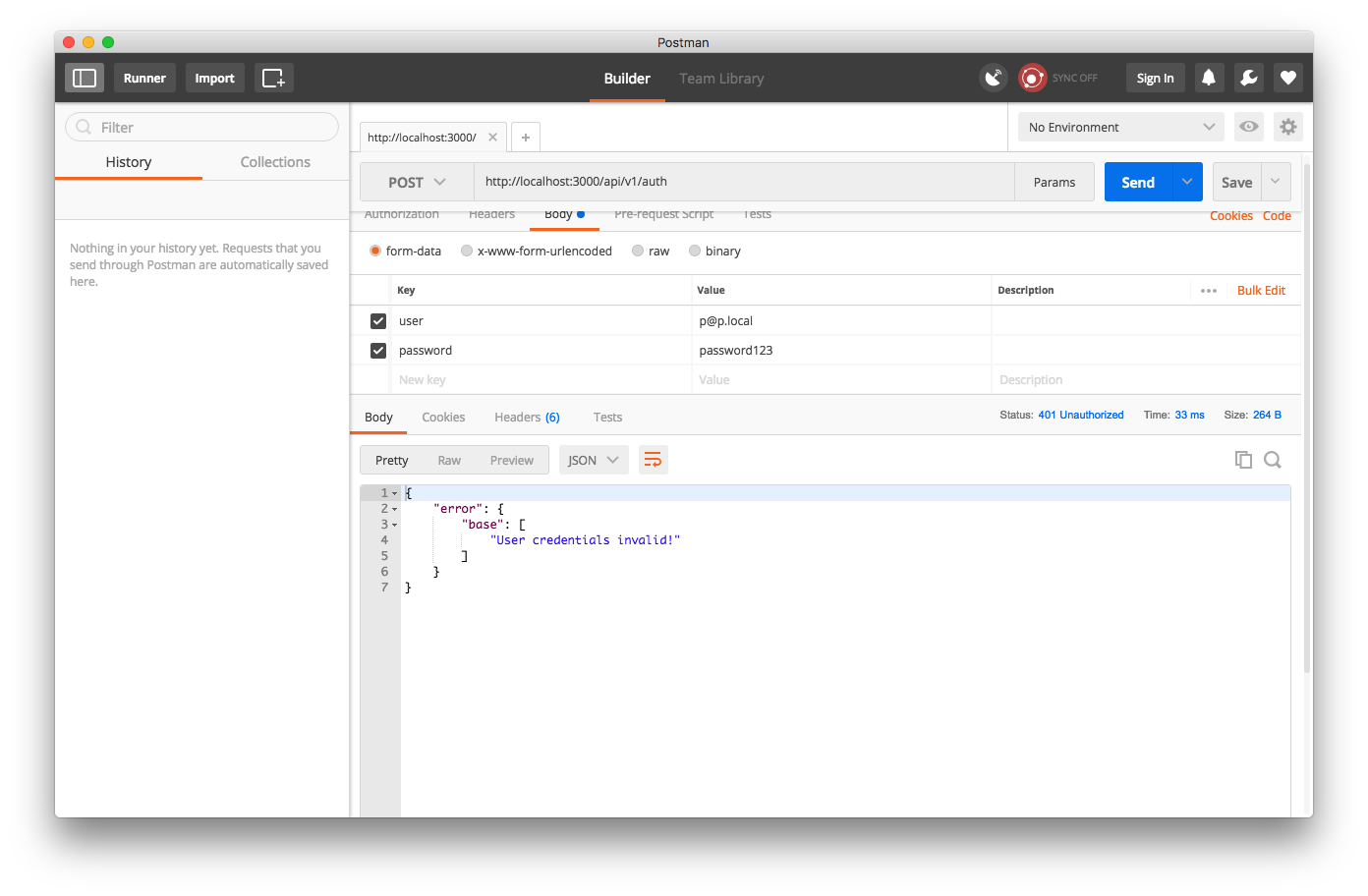

Now when I try to log in with a nonexistent user, I get an Unauthorized status:

But when I create this user in the console,

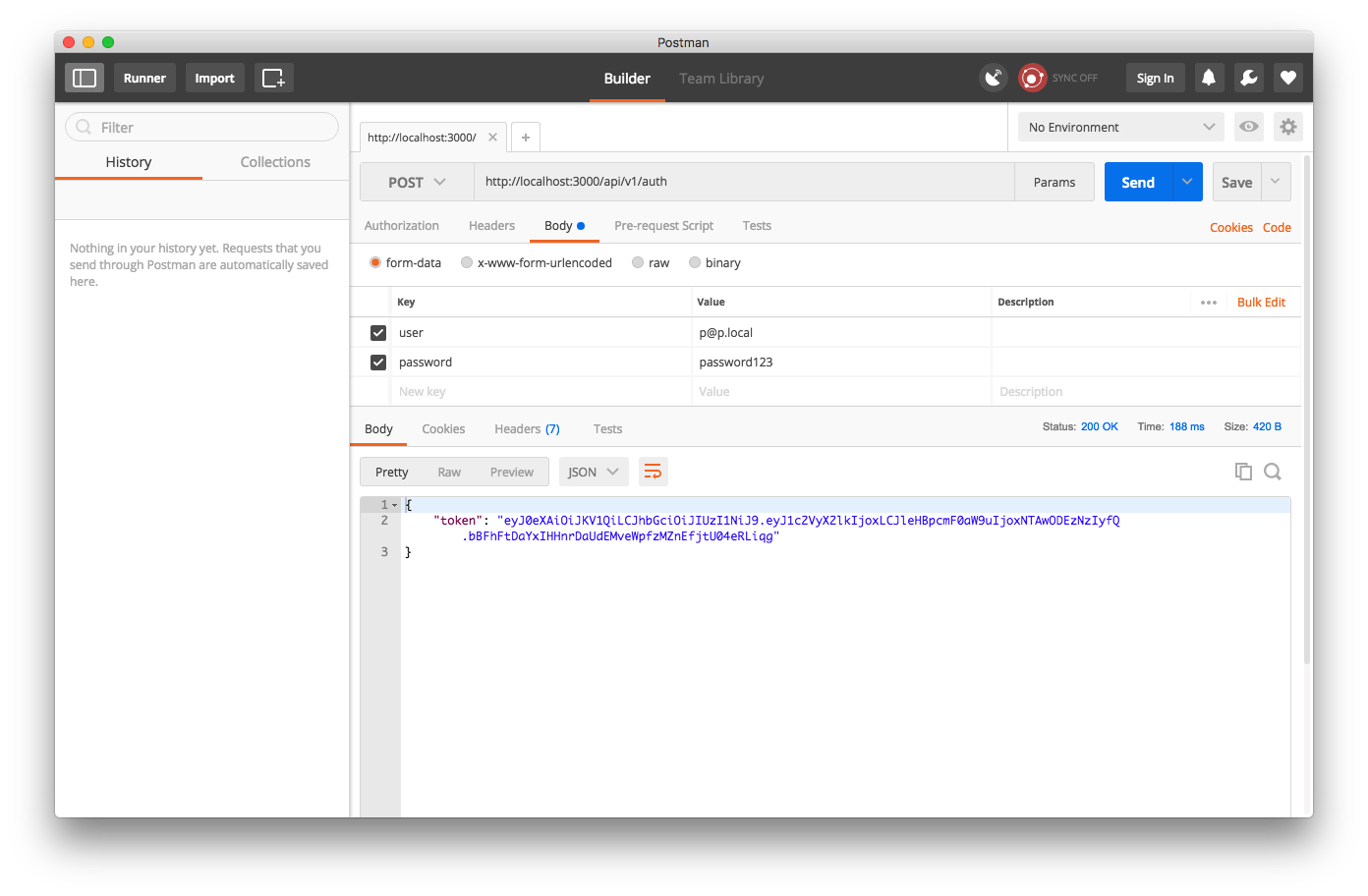

User.create(email: 'p@p.local', password: 'password123')

and try again,

Sweet! A token!

Locking it down

We need to do a couple more things:

- decode the token from headers,

- check it against database for users,

- check if it’s not expired.

We can confine this to another command:

class DecodeAuthenticationCommand < BaseCommand

private

attr_reader :headers

def initialize(headers)

@headers = headers

@user = nil

end

def payload

return unless token_present?

@result = user if user

end

def user

@user ||= User.find_by(id: decoded_id)

@user || errors.add(:token, I18n.t('decode_authentication_command.token_invalid')) && nil

end

def token_present?

token.present? && token_contents.present?

end

def token

return authorization_header.split(' ').last if authorization_header.present?

errors.add(:token, I18n.t('decode_authentication_command.token_missing'))

nil

end

def authorization_header

headers['Authorization']

end

def token_contents

@token_contents ||= begin

decoded = JwtService.decode(token)

errors.add(:token, I18n.t('decode_authentication_command.token_expired')) unless decoded

decoded

end

end

def decoded_id

token_contents['user_id']

end

end

Whew, another mouthful! It extracts the contents of the Authorization header (expecting it to contain something like Bearer token.goes.here, checks whether a user with a given ID exists. We’re also assuming that when JwtService returns nil, it’s

because the token has already expired (according to the exp reserved claim). If anything goes wrong at all, it just registers an error and bails.

We can then get ourselves a nice concern to include in our application controller:

class NotAuthorizedException < StandardError; end

module TokenAuthenticatable

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

included do

attr_reader :current_user

before_action :authenticate_user

rescue_from NotAuthorizedException, with: -> { render json: { error: 'Not Authorized' }, status: 401 }

end

private

def authenticate_user

@current_user = DecodeAuthenticationCommand.call(request.headers).result

raise NotAuthorizedException unless @current_user

end

end

It’s also important to add

skip_before_action :authenticate_user

to our AuthsController, or we will reject users trying to authenticate because they aren’t authenticated.

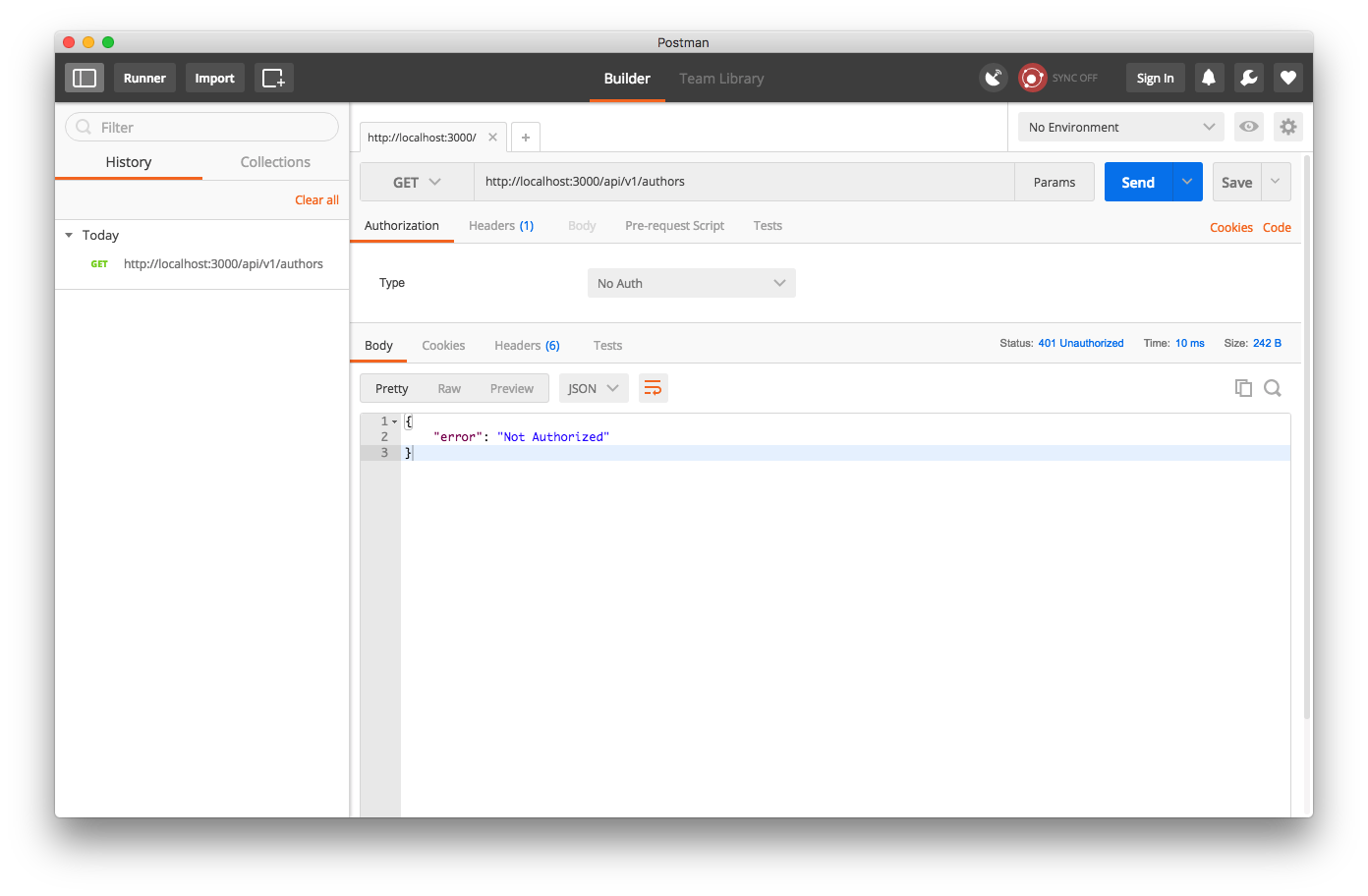

Now if I try to get a list of authors in Postman not passing in an authentication header, I get rejected:

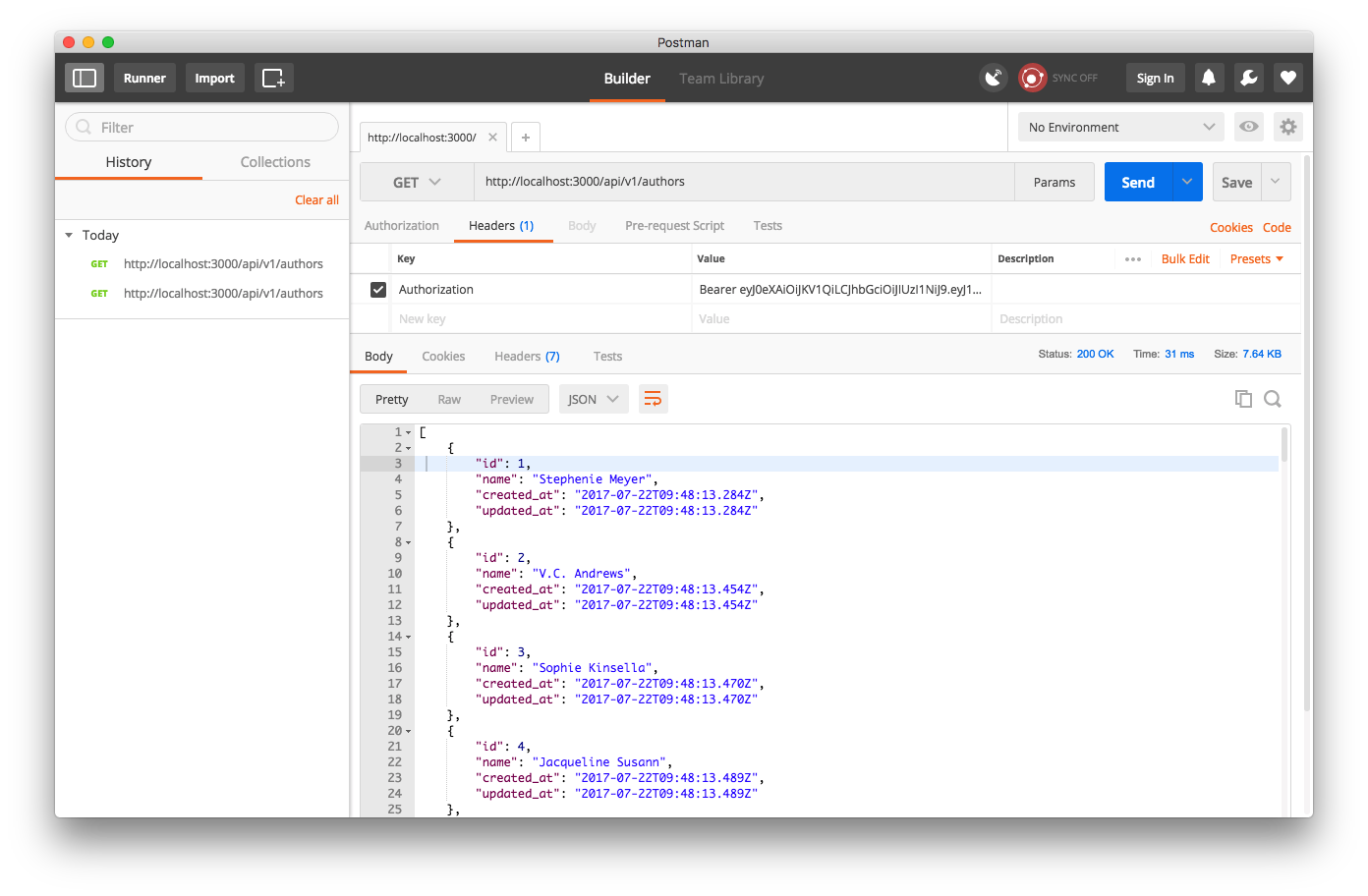

But if I do pass this header, I’m approved!

Administrative access

One more thing: currently any logged in user can edit books. That’s not great. We’ll need to check for admin privileges before that.

We’ll add a simple authorization-checking function in another concern:

module AdminAuthorizable

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

included do

rescue_from NotPermittedException, with: -> { render json: { error: 'Not Permitted' }, status: :forbidden }

end

def authorize!(action)

raise NotPermittedException if action != :read && !current_user.admin?

true

end

end

Big thank you to Никита Василевский for pointing out that I left a bug in this code!

Now we can use authorize! :read in our index and show actions, and authorize! :create, authorize! :update and authorize! :destroy elsewhere. Simple yet effective!

Closing thoughts

We did a lot of things by hand today. We could have plonked in Devise, simple_command for the command objects (I recommend you look it over if you haven’t already - our commands are heavily modeled after what they’re doing!), and e.g. cancancan for the role-based auth. The point, however, is to learn how to do things yourself, especially in fun-time projects - it removes a lot of magic from the gems you’re using in large, production-level apps.

As always, the state of the project after this part can be found on GitHub at paweljw/bookstore-backend.

We’ve started adding tests in this part, too. We’re not exactly doing TDD here - and that’s totally fine when learning (unless you’re learning TDD, of course!). It was important to get the basic API and auth working in the first place so that we know what we’re testing. We’ll talk about testing Rails API apps next time. See you then!

And once again, special thanks go out to Никита Василевский and Ylan Segal for corrections!

Top image credit: https://pixabay.com/p-406986/ (CC0)